Del Close Doc Charts The Lord of Misrule Who Shaped Contemporary Comedy

By Liam Lacey

Rating: B

A viewer might come away from Heather Ross’ creatively free-wheeling, celebrity-filled documentary, For Mad Men Only: The Stories of Del Close, with the impression that the improv comedy movement from the 1950s was primarily the work of one troubled genius. That would be misleading.

As more modest starting point is The New York Times obit of Del Close, who died in 1999 at the age of 64, where he was described as “one of those show business legends whose influence was felt far beyond his limited fame.”

The Times obit went on to recount how Close had a farewell party on the day before his death, where he bequeathed his skull to Goodman Theatre to star as Yorick in their next production of Hamlet. Clearly, a fellow of infinite jest.

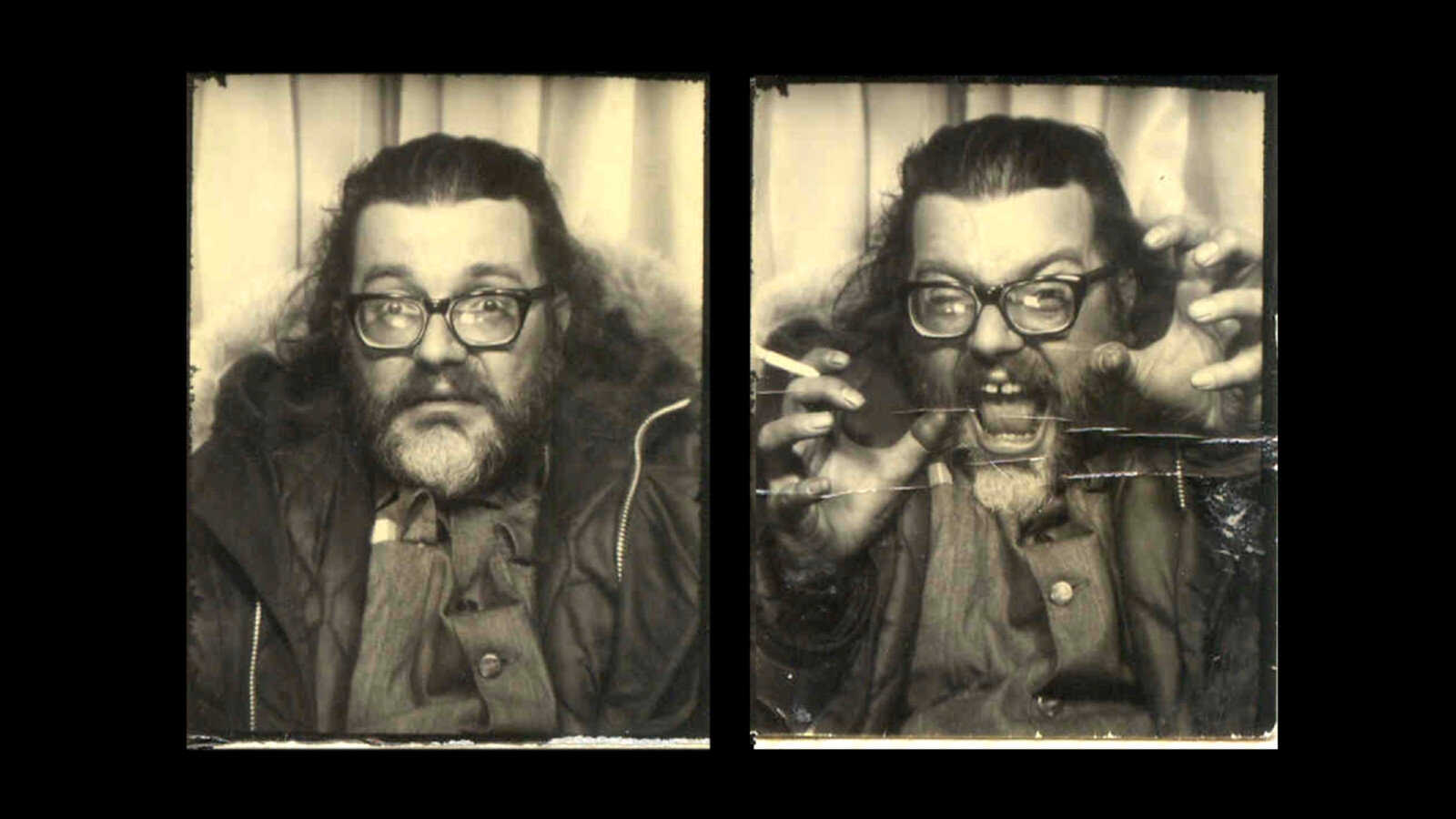

The film covers many of the Del Close stories, about a man whose creative powers and anxiety disorders were apparently inextricable. Close was a hippie, gap-toothed wild man who practiced witchcraft, a bipolar genius who worked with Mike Nichols and Elaine May in their salad days, who became a mentor to many of the most famous names in late 20th century comedy.

Those names include John Belushi, Bill Murray, Bob Odenkirk, Adam McKay, Harold Ramis, Amy Poehler, Chris Farley, Tina Fey and Mike Myers. Many of these figures are seen in archival footage, praising Close for teaching them to reach beyond punchlines, to be bold onstage, to always say yes to a suggestion and never make the safe choice.

Certainly, Close didn’t play it safe in his own life. He struggled with drug abuse, spent time in psychiatric hospitals, and travelled with Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters.

PROUDLY SUPPORTS ORIGINAL-CIN

Most importantly, Close was at a central figure in the high-risk of improvisational comic theatre movement over five decades: The Compass Players in the mid-1950s; The Second City in the Chicago and later, Toronto; San Francisco’s The Groundlings; Los Angeles’ The Committee; and Chicago’s training and performance centre, ImprovOlympic (later IO Theatre) in the last two decades of his life.

Though he was also a stage and screen performer, Close’s key importance was as a coach and inspirational figure, qualities that can be talked about but are hard to show on film. To bring her character to life, Ross does some creative play with the fiction/fact wall, using Close’s own words.

In 1987, DC Comics hired John Ostrander and Close to write a horror anthology series called Wasteland, based on Close’s stories. There’s a lot of animation in the film inspired by that comic, but more interesting are dramatizations of brainstorming sessions with Ostrander (played by Josh Fadem), editor Mike Gold (played by Veep’s Matt Walsh) with James Urbaniak (excellent) as Close, spitballing grotesque and absurd ideas.

Not everyone was enamoured of Close’s brand of mad genius. Another comic master, SCTV’s Dave Thomas, relates his experience in the seventies when the increasingly unstable Close was sent to Toronto (exiled to the frozen north in the documentary’s perspective) to work with the fledgling local Second City cast.

Thomas says Close’s reputation as a “delicate basket of eggs” preceded him, lived up to the hype, pushing the line between comedy and personal therapy. Thomas’ insight is that Close went for the “gasp” rather than the laugh is intriguing, and marks what appears to be an essential difference between the early edge-pushing Chicago Saturday Night Live-style and the buttoned-down Canadian approach, which culminated in the brilliant Second City Television.

Consistent with Close’s monster sacré persona, the film’s script slips into flippant hyperbole when narrator Michaela Watkins, reading a script by Heather Ross and Adam Samuel Goldman, describes Close as “the guru who discovered a new art form: improvised comedy” or claims that “Del’s path of self-destruction has cut through almost every seminal comedy moment of the past 60 years.” (Sorry, Monty Python, Richard Pryor, Lily Tomlin, Robin Williams, Steve Martin and everyone else).

There’s no doubt that spotlighting Close’s reputation in our recent cultural history is worthwhile. But the documentary is unjust in ignoring such seminal figures as acting coach and academic Violin Spolin, who developed and wrote the bible on the subject (Improvisation for the Theatre).

Or, her son, Paul Sills, who put improv theory into commercial practice by co-founding The Compass Players and The Second City. Or his artistic partner David Shepherd (Compass Players, ImprovOlympic, The Canadian Improv Games), and dozens of other people who developed this great late-20th century art form.

When it comes to the collective art of improvised theatrical comedy, “genius” has happened repeatedly and usually in clusters.

For Madmen Only: The Del Close Story. Directed by Heather Ross. Written by Heather Ross and Adam Samuel Goldman. With Josh Fadem, Mike Gold, and James Urbaniak. Available from July 27 on Hot Docs digital cinema.