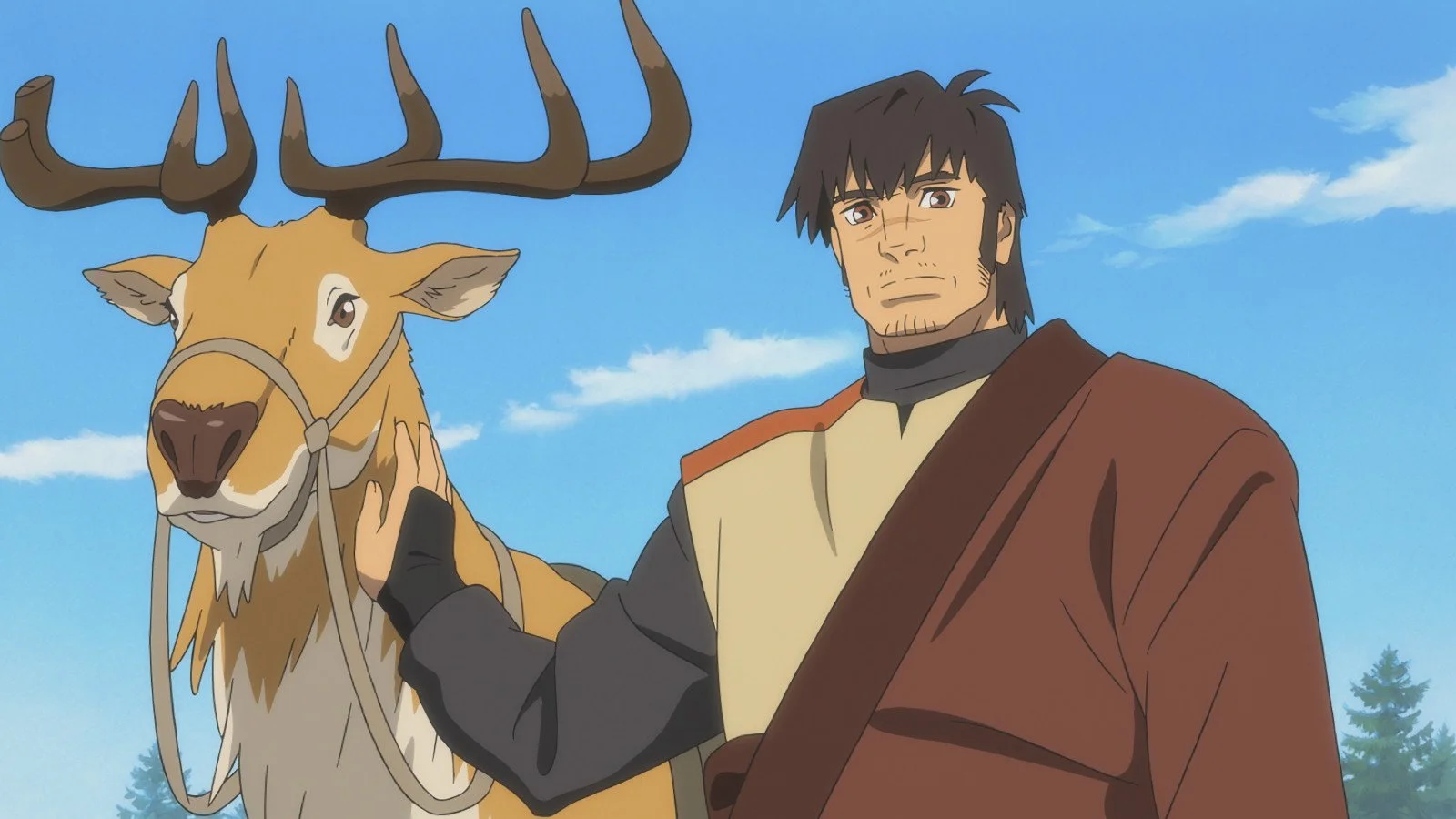

The Deer King: Japanese Weaponized Deer and The Fever Dogs of War

By Liam Lacey

Rating: C+

Cartoons about anthropomorphic animals are popular with kids around the world, though often with distinctly local significance and origins.

You hear the name “Deer King,” and you might think Bambi, the 1942 Disney classic, in which the orphaned fawn ends up as the Great Prince of the Forest. The Lion King from 1994, which lead the Disney revival, followed a similar story.

But the Japanese animated film The Deer King draws from a very different mythology, a military epic involving imperialism, ethnic conflict, and bio-warfare. The film is co-directed by two alumni of the famed Ghibli studios, Masayuki Miyaji and Masashi Ando, and based on a fantasy series from ethnology professor Nahoko Uehashi.

Her story tells of two antagonistic tribes — the dominant, Zol and their ancient rivals, the Aquafa — in an uneasy peace, filled with suspicion and superstition. For some reason, only Zol are susceptible to a fatal condition known as the Black Wolf Fever, which has been dormant for a decade.

In the opening sequence, the camera descends through a yellow honeycomb pattern in the earth. We go down into an underground salt mine, worked by prisoners. Shortly after the start, a pack of mad dogs swarm through the mine, biting everyone in their way, causing most of them to instantly die.

Much of what comes next is frustrating to follow, combining an overly dense plot and poorly translated subtitles. There are two survivors from the mine attack: a burly prisoner, Van — leader of a warrior group called the Lone Antlers, who rode on deer — and a girl toddler who he rescues named Yuna.

Although Van is bitten by one of the dogs, instead of killing him, it gives him super-natural strength. Soon after escaping the mine, he finds a special deer called piuika, a military-grade steed, which he and Yuka ride upon.

There’s a longish stretch in which Van bonds with the Yuna while living in a village and domesticating and training other deer; she learns to milk the special deer. After a while, she calls him “dada” and everyone dances a jig around a fireplace at night.

But Van and Yuna are chased by a trio of envoys from the royal court, including an androgynous priest-doctor, a female ace-archer and tracker, and a comically thuggish bodyguard. The doctor, Hosalle, who is a secondary hero, struggles to establish that there is a scientific rather than supernatural explanation for Aquafa people’s immunity to the disease.

Visually, The Deer King is lushly surreal, with royal surveillance balloons that look like giant eyeballs floating over misty mountains and vistas covered in bile-green lichen. The dog attacks are particularly good, beginning with a swirling inky tide from which the animals’ dark silhouettes emerge. These images tantalize, but without satisfying, like a trailer for a narrative that would work better as a long-form series.

The Deer King. Directed by Masshi Ando and Mijayji Masayuki. Written by Taku Kishimoto, adapted from the series by Nahoko Uehashi. In theatres on July 15.