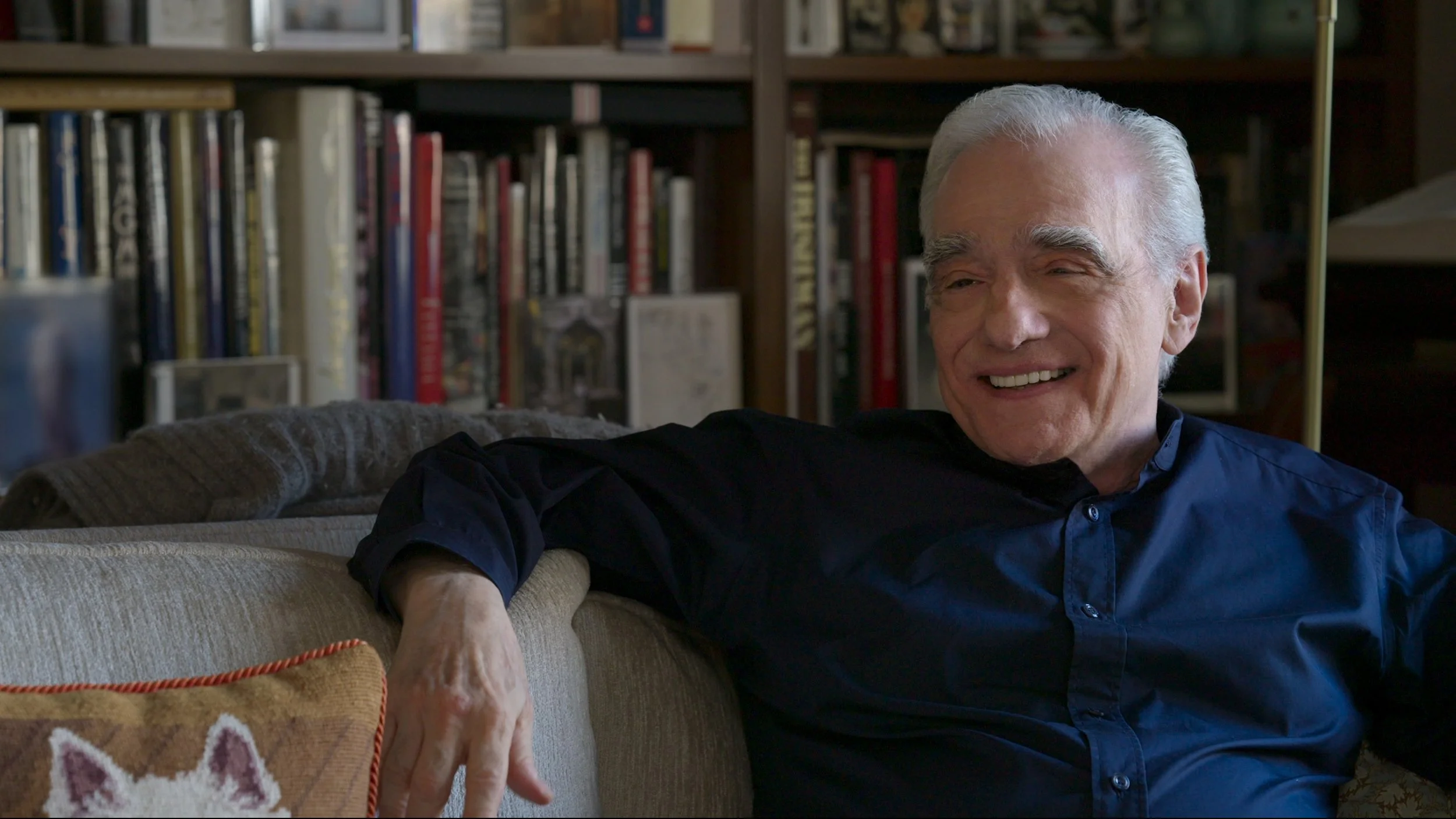

Mr. Scorsese: A Film Portrait of the Great Italian American Director. Yes, He’s Talking to You

By Liam Lacey

Rating: A

Martin Scorsese may be “the greatest biography in American film since that of Orson Welles," wrote David Thomson in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, "and the most painful."

As most filmgoers know, the artistic highs of Scorsese’s filmography — Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street, to name a few — are inextricably bound with his obsessions and his Catholic sense of good and evil.

The connection between his life and filmography is explored in rich detail in the compulsively watchable new Apple TV+ series Mr. Scorsese by filmmaker Rebecca Miller (The Ballad of Jack and Rose), which follows Scorsese from childhood to the preparations of his 2023 film, Killers of the Flower Moon.

Along with Miller’s own pertinent questions to Scorsese, she supports the portrait with an army of interview subjects. They include Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis, Sharon Stone, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, Spike Lee, Paul Schrader, writer Jay Cocks, film editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, musicians Robbie Robertson and Mick Jagger and wives, daughters, childhood friends and Scorsese’s late parents.

An inveterate mythmaker, Scorsese marks his own fall from paradise as an incident in Queen’s when his father, Charles Scorsese, was involved in a public fight with his landlord (“I remember someone brought out an ax.”)

The humiliated Scorsese family was banished back to a crowded apartment in Manhattan’s Little Italy, close to the squalor of the Bowery and a scene of mob violence. Growing up there as an undersized, asthmatic child who wasn’t allowed to play outside, Scorsese would watch the streets below from the high angle of his bedroom window.

As a child he was drawn equally to the Catholic church and the cinema, an air-conditioned refuge where his father would take him on sweltering New York summer days. (His childhood storyboards for imaginary epic films are astonishingly precocious.) Little Marty was, he believed, a bad boy who aspired to be a priest but after being asked to leave his pre-seminary school after a year, he opted for the profane vocation of filmmaker.

Both the cinema and the church left their imprint. Catholic iconography became part of his recurrent visual vocabulary, and the residue of his immersion in film history resonates through everything he has done since. He developed an encyclopedic memory for directors, genres and individual shots from different films, both the Hollywood narratives and foreign cinema, including with the Italian neorealist films his family and neighbours would watch on the television.

Even when Scorsese seems to be coasting as a filmmaker — say, The Aviator or The Departed — he is in command of vast reservoir of style and technique.

Scorsese’s first feature, Who’s That Knocking on My Door?, shot while in he was in college over several years, got him attention. The film progresses through his work with exploitation director Roger Corman, his guidance by filmmaker-actor John Cassavetes and his highs and lows of the 1970s, culminating in his near-death from cocaine abuse.

Scorsese’s prolonged cocaine binge, in concert with The Band’s Robbie Robertson, helps explain why the musical New York, New York is so good in sequences and hard to grasp as a whole. Apparently, we should have seen the four-and-a-half-hour cut.

Scorsese’s friend, the writer Nicholas Pileggi — who wrote the book on which Goodfellas was based — says that Scorsese’s theme is the underdog who rises up through the system and often finds that success and failure coincide.

Scorsese is, despite his Catholic upbringing, no saint, prone to anger and chronic self-doubt. After each setback (The King of Comedy, Bringing Out the Dead), Scorsese says he felt like a social pariah, a humiliated outcast. Isabella Rossellini, his second of five wives, recalls him waking up in the morning swearing, or trashing the furniture in their home in blind rages.

Miller’s film lays down plenty of threads for further inquiry, and in some ways, one might wish the series were twice as long. The question of Scorsese’s larger cultural influence is impossible to quantify; the many clones of Taxi Driver’s evangelistic incel Travis Bickle haunt the internet. But it’s easy to see how his early eighties’ films like After Hours and The King of Comedy mapped out a path of independent cinema, in contrast to special effects–driven extravaganzas that came to dominate the mainstream.

Quentin Tarantino, who doesn’t appear in the film, lifted parts of the overdose scene in Pulp Fiction from Scorsese’s short 1978 documentary, American Boy: A Profile of Steven Prince. We hear from a couple of the auteurs of the current generation, including Ari Aster (Hereditary, Midsommar) and both the Safdie brothers (Uncut Gems) who have scrutinized Scorsese’s films and biography.

Josh Safdie calls Scorsese “almost a method director” who identifies so strongly with his films he dresses like the characters when he’s shooting, an approach Safdie considers “very dangerous.” Scorsese’s account of his mental breakdown shooting Shutter Island attests to the risks.

After making his three-and-a-half-hour documentary on George Harrison, Living in the Material World (2011), Scorsese says he discovered the mental health benefits of meditation, and his daughters from different marriages attest that he has become a calmer man with age.

Though Miller doesn’t make much of it, in a late scene in the final episode, we see Scorsese, in mid-conversation, quickly reach for his inhaler that he keeps at arm’s reach, and we’re reminded of a man who has spent most of his entire life having to remember to catch his breath.

Mr. Scorsese. Directed by Rebecca Miller. Available on AppleTV+ October 17.