Original-Cin Talk: Alan Zweig on Suicide and His Film Love, Harold, at Rendezvous With Madness

By Jim Slotek

It spoke to the stigma that surrounds suicide when Alan Zweig, the director of the doc Love, Harold, decided to use some of his production budget to hire a researcher to find relatives and friends of suicide victims.

“I found that the researcher, one of Canada’s most experienced, couldn’t find, through normal research methods, one person for me to get in the film,” the prolific documentarian says.

“They’re not publicized, they’re not put in the paper, people say ‘died suddenly.’”

As a result, Love, Harold, a feature at this week’s arts and mental health film festival Rendezvous with Madness, is peopled entirely by friends and acquaintances of Zweig, who came together almost organically.

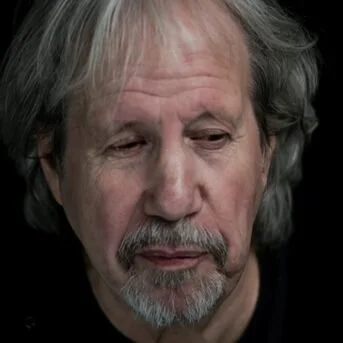

Director Zweig and John at the scene of their friend Jim’s suicide in Cambodia

Zweig was already pondering the death in Cambodia of Jim, a friend he hadn’t seen in 20 years, and whom he considered to be the least likely person who would take his own life.

“After Jim killed himself, there’s a woman in the film Martha Baillie. She’d written a book with her sister called Sister Language, and we were all going to the book launch. And her sister Christina killed herself between the book coming out and the launch.

“Martha is a very close friend of my girlfriend, my partner, so that was like, I don’t know, one step.

“And then there was a woman I know who phoned me and said, ‘Do you remember my friend Jeremy? I always thought you guys would get along. He was kind of a curmudgeon. I really wanted you to meet.’

“I was like, ‘Yeah okay.’

“’Well, could you go with me to his funeral today? Because he killed himself.’ I hadn’t even decided to make a film yet.”

Alan Zweig

Among the first to convince was John, a drummer who shared his friendship with Jim (who’d played guitar), and who, unlike Zweig, wasn’t surprised about the suicide.

“I didn’t ask people, ‘Do you know someone who killed themselves? Do you have a friend who killed himself? But I did, in a more casual way, do that. And all but one person in the film was either a friend or a friend of a friend.

“One person who’s in the film did it because she knew my films.”

And even then, stigma sometimes got in the way. “One man told us, ‘Yes, my son killed himself. But if I’m in your film, my brother will find out my son killed himself, and we told him another story.’ Effectively, he said, ‘I can’t be in your film because nobody knows the truth.’”

The truth, however, often longs to be released. Zweig operated with a personal rule that he would not ask how or why the individuals took their lives. This was not to be a film about suicide, but about its effects on the living – a mother mourning her 19-year-old daughter, a middle-aged man still traumatized by the long-ago death of his father (whose suicide was passed off as a heart attack).

Zweig would ask, “How are you dealing with it?”

“Now when I ask that, some of them revealed how the person did it or speculated on why. That’s how they are dealing with it.”

I reminded Zweig of the irony of having made a 2013 film called 15 Reasons to Live. “I didn’t think about that when I started. But yes, that movie was inspired by somebody trying to convince themselves that life was worth living.

“I don’t think showing them 15 Reasons to Live would convince them at that moment. But one person in the film, the young man Jamal is talking about his friend Ian, and he said “I don’t think Ian wanted to do the loop again.” That’s the most profound thing in the film because he’s talking about a young man I believe in his forties

“And I think there were four or five people in the film who were around that age who had experienced struggles, but had overcome, had some success and then were back down having lost everything – whether it was your girlfriend, meet a woman, you move in, she kicked you out, you’re back down. Do you want to go through that loop again?

“And I’m afraid of saying anything triggering, but personally I can understand that. Vinyl was basically when my career started, and I was 48, and before that I did the loop a few times.

“I wish I could tell them, ‘Hey, I got out of it. I did the loop one more time and it worked. I have a career, I have a daughter, I have an ex-wife, I made it, kind of.’”

And what lesson did he learn from uncovered truths about Jim? “My lesson would be, it’s easy not to really know your friends. It’s easy just to know something on the surface and go with that. Maybe you should look a little deeper.”

RENDEZVOUS WITH MADNESS

Billed as the first in the world and largest arts and mental health festival in North America, Toronto’s Rendezvous with Madness was founded by psychiatric nurse Lisa Brown with a mandate to use the arts as an entry point for mental health awareness.

The 33rd edition of the festival opens on October 23 with Blackfoot director Damien Eagle Bear’s #skoden, about his search to find the man behind a meme.

In 2010, a man named Pernell Bad Arm went viral in a video on the ‘Net, apparently intoxicated and fists-up, shouting “Skoden (Rez-speak for “let’s go, then!”).

Initially, a target of racial ridicule, young Indigenous people began adopting “Skoden!” as a rallying cry. And Eagle Bear realized that Bad Arm had been one of his subjects when he undertook a project to profile the occupants of a Lethbridge, Alberta shelter.

As a project, he had been overcome by the number of tragic stories. But Pernell gave him focus to tell the stories of both the individual and the community of laregely disenfranchised community from which he came.

A breakthrough movie for Eagle Bear, #skoden debuted earlier this year at Hot Docs and is comes highly recommended by Original-Cin.

Other films of note on the Redezvous schedule include The Secret of Me, a recent favourite at South by Southwest, about a biological male, raised as a girl, the victim at birth of forced gender designation. Shuffle, about recovery-centre insurance fraud, recently won the SXSW Documentary Award, and Paul, about a 300-pound man with social anxiety a compulsion to dote on someone who doesn’t return the affection.

The 2025 Festival runs from October 23 – November 2, primarily at the Workman Arts/CAMH Auditorium, with 11 feature films, live performance programming and a music showcase and night market.

CLICK HERE for more information, streaming details and ticketing.