Cover Up: The Atrocities Seymour Hersh Has Seen and Exposed

By Liam Lacey

Rating: A

The use of the word “storyteller” to describe film and television content creators is over-used and often pretentious. But there are times when the shoe fits elegantly, as with the works of documentarian Laura Poitras.

Watching each new documentary by Poitras (The Oath, Citizenfour All the Beauty and the Bloodshed), is to lock into a mental track, with a balance of structure and pace, coherence and surprise, intellectual and emotional engagement.

The My Lai massacre of villagers in Vietnam is Hersh’s best known bombshell

Her latest compelling documentary, Cover-Up (in theatres now before coming to Netflix on Dec. 26), is a retrospective on the career of legendary investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, co-directed with Hirsch’s longtime associate Mark Obenhaus.

Now 88, Hersh has an unparalleled history as an investigative reporter, having exposed the U.S. government’s criminal abuses and cover-ups for more than half a century. He’s best-known for exposing the My Lai massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam war, and, in 2004, the revelations about of the U.S. torture of prisoners in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

Cover-Up begins back in 1968 with one of Hersh’s earliest, now largely forgotten scoops, of a U.S. Army aerial nerve gas test in Dugway, Utah, that killed 6,000 sheep and sickened local farmers. It’s a story that established his long-running quarrel with the military and its secrets.

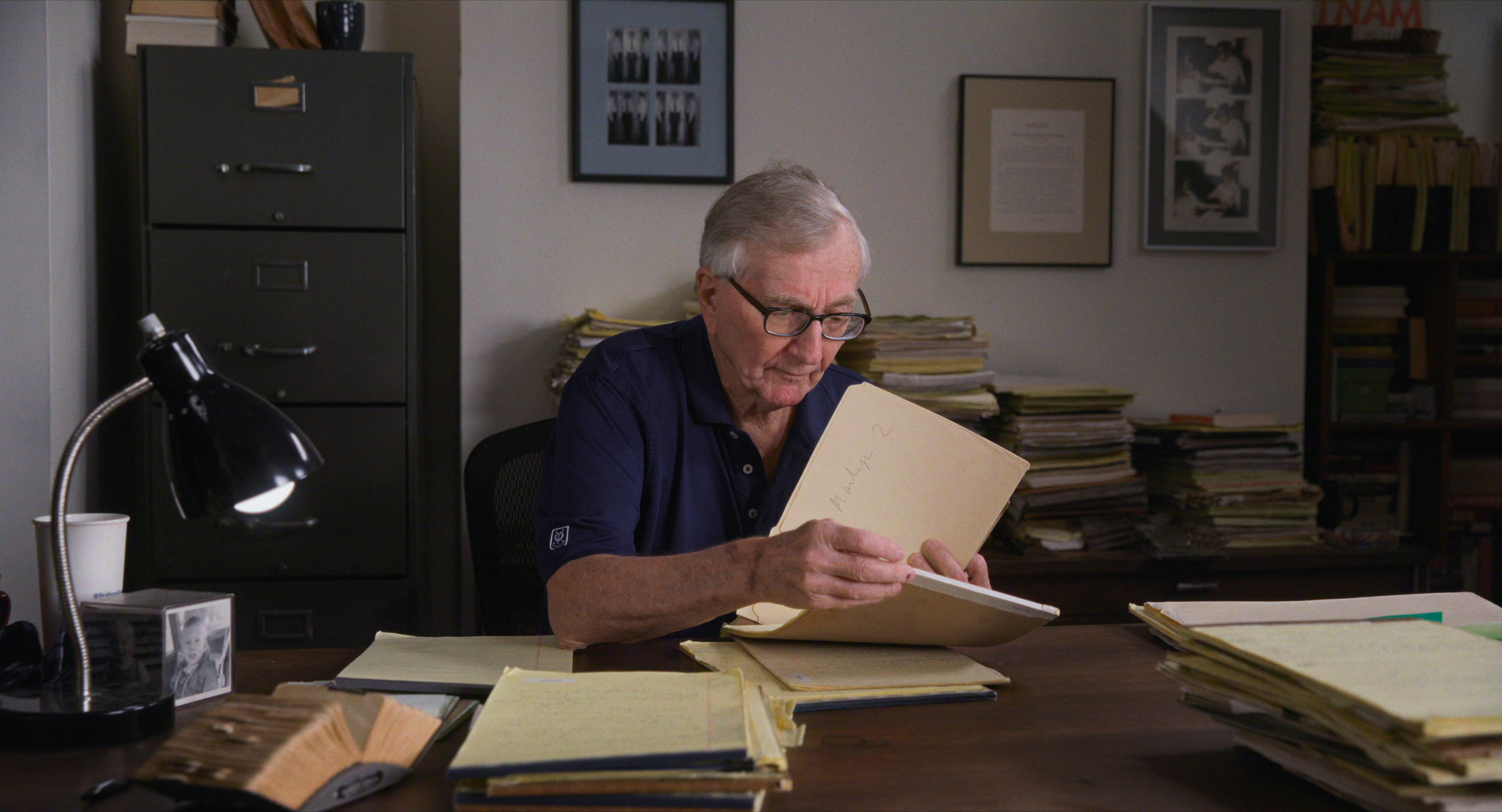

Hersh in his home office

We jump to present-day Hersh at his desk in his home office, surrounded by hills of boxes and stacked papers, interacting with the off-screen interrogators with a combination of snappish defensiveness and sometimes tearful vulnerability:

“You’d love to talk about sources. I prefer not to talk about sources,” he blusters. “I don’t psychoanalyze those who talk to me, just like I don’t psychoanalyze myself, thank God. Which you want me to do, I know, but I’m not gonna go there.”

Part of the premise of Cover-Up is that Hersh is the reluctant subject of the documentary that Poitras has pursued for 20 years, though his insistence that he doesn’t want to be the story is somewhat undermined by his 2018 best-selling memoir, Reporter, and by a history of public combativeness with his critics.

Perhaps, as Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. As a colleague says of Hersh, the only consistent thing about him is his illegible handwriting.

Poitras’ film unfolds in loosely chronological chapters, hopping back and forth in time as certain themes are touched upon. The central early chapter follows how Hersh stumbled on the story of the Mŷ Lai massacre, after quitting the Associated Press after a fight with an editor (something of a career refrain).

It’s a good thriller plot, involving crossing the country on borrowed money, living in his suit, random phone calls and anguished confessions. The massacre of hundreds of Vietnamese villagers was a hugely influential factor in the opposition to the U.S. involvement Vietnam war, and Poitras has an abundance of archival visual material here to demonstrate its impact.

We return to Hersh in his office, receiving a phone call from a woman who says she has returned from Gaza as a researcher, with evidence of Israeli soldiers deliberately killing Palestinian women and children. The story’s on background: She’s not quite ready to have him run with it.

We switch back in time to Hersh’s background biography, growing up on the south side of Chicago, where his father, a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania who arrived in the U.S. in 1930, ran a dry-cleaning business — and communicated in either “silence or rage.” His extended family was killed in the Holocaust, a subject Hersh says was never discussed in his home. We’re left to provide our own psychoanalysis.

That’s followed by a quick summary of Hersh’s career, his instant addiction to journalism, a stretch at Associated Press covering the Pentagon, and after, with a Pulitzer to his name, a gig at the New York Times.

The paranoid Cold War 1970s were a great time for investigative reporting, including the Watergate scandal, which the New York Times reluctantly assigned Hersh to, months after Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had broken the story for The Washington Post. (Woodward expresses his gratitude for Hersh for pushing the story forward.). Further investigations of the CIA led to front-page scandals and resignations, revealed the agency’s role in spying on U.S. citizens, and its notorious history of mind-control experiments and foreign assassinations.

In the late ‘70s, though, Hersh became aware that The Times was more amenable to covering government wrong-doing than the corporate kind. When he and investigative partner, Jeff Gerth, learned that the Times’ executive editor Abe Rosenthal had received a loan at a favourable interest rate from the newspaper’s board of directors, he confronted his boss: “My lawyer says it’s okay.” said Rosenthal. “That’s what every crook I’ve ever talked to in my life has said,” Hersh countered. He left the Times soon after in 1979, noting there was no goodbye party.

In his memoir, Reporter, Hersh wrote that his golden rule was, “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” One might wonder if Poitras is sufficiently skeptical? Certainly, there were stories that hurt Hersh’s reputation, either because he got them wrong or because of the way he conveyed them. The filmmaker pushes into this controversial areas very gently (“This isn’t easy for you…” she says off-camera).

One of those controversies, his 1997 book, The Dark Side of Camelot, on President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, earned scathing reviews for its gossipy tone and use of anonymous sources, while being overshadowed by a scandal regarding forged love letters between Marilyn Monroe and the president. More recently, Hersh made the unverified claim that Americans were responsible for the 2022 sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines carrying natural gas between Russia and Europe. (An ongoing German investigation points to a pro-Ukrainian group). Hersh was also one of a group of contrarian journalists who claimed that rebel Syrian forces, not President Bashar al-Assad’s military, used chemical weapons against the civilian population (contradicted by United Nations investigators and other researchers). In the film, he admits his error about al-Assad, with a belligerent mea culpa: “Let’s call that wrong. Let’s call that very much wrong. If I made a claim in previous interviews to being perfect, I now withdraw it.”

In the early 2000s, under the guidance of New Yorker editor, David Remnick, Hersh wrote a series of important stories about the intelligence failures of 9/11 and the lies about Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction that justified the U.S. invasion in 2003. But these stories which offer few visual opportunities for a film and get relatively short shrift here.

In contrast, his 2004 blockbuster exposé of the Abu Ghraib prison torture, was highly dependent on visual evidence. One of the documentaries revelations is the source of those photos, Camille Lo Sapio, a woman whose daughter-in-law borrowed her laptop when she was deployed to Iraq, and returned with pictures from her time as a guard at Abu Ghraib prison.

The Abu Ghraib sequence is followed by Hersh, once again back in his office, receiving an update from his Gaza source about the IDF targeting civilians. His next atrocity story awaits, though now on Substack rather than a major media publication.

Near the film’s end, Poitras circles back to the aftermath of the Mŷ Lai exposé. Lieutenant William Calley, the key figure in the massacre, who was convicted of the murder of 22 civilians and ordering the deaths of several hundreds more , became a heroic martyr to the right. He was released to house arrest after serving just four months in stockade and eventually to freedom.

What is Poitras’ reason for structuring the film in this circular way? The obvious point is that the war against state violence is not won but occasionally revealed, rebuked and exposed to shame. Hersh says he cannot be reconciled to living in a country where committing atrocities, and lying about them, becomes acceptable. Poitras’ film reminds us that, not only his heart, but his outrage, is in the right place.

Cover-Up. Directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus. With Seymour Hersh. Cover-Up is currently available in selected theatres in Canada and the United States, including VIFF Centre in Vancouver (Dec.14-17) and Cinema Moderne, Montreal (Dec. 13-15). It will be available on Netflix on Dec. 26.